Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

The Drawn Visualisation of the More Subtle but Powerful Effects of Depersonalisation

*Corresponding author: John Robert Burns, John Burns Illustration, 54 Holmfield Road Coventry, West Midlands, CV2 4DE, UK.

Received: July 07, 2022; Published: September 02, 2022

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2022.17.002307

Abstract

Keywords: Depersonalisation; Pharmaceutical Side Effects; Post-Viral Syndrome; Solipsism

Introduction

Having worked as an animator, graphic designer and illustrator for clients in the medical and pharmaceutical industries, I have been required to visualise aspects of pain control, food-poisoning, gastric and digestive disorders, chemi-luminescence, hepatitis treatments, deodorant actions and other physical and medical conditions and treatments.

This has often required the visualisation of qualified medical themes, details and theories that have, at the time of production, been sometimes agreed between contributing medical and scientific professionals and at other times have been the subject of differing opinions and points of view.

Whilst this type of situation is very much to be expected within a field of constant research and development, it can require a certain visual convergence of disparate points of view into a pictorial depiction of complex structures and processes within a generally accepted form, in time to meet production and delivery deadlines.

As an educator at post-graduate level, such scenarios are brought sharply into focus when students set out to produce project work that also relies heavily on currently developing research and knowledge.

Whilst producing animated artworks for pharmaceutical companies that were particularly involved in pain-control treatments – and in reading the supplied and required specialist texts concerning the subject – I became aware of the documented inability of even the most articulate patients to adequately describe, in verbal or written form, the physical and mental sensations that they were experiencing under the effects of certain conditions or treatments.

Having personally experienced the unsettling and often bizarre side effects of certain pharmaceutical treatments, together with the physical and exhaustion-based phenomena associated with post-viral syndrome - and the debilitating and confusing changes in awareness brought about by prolonged jet-lag - I can appreciate the difficulties that people experience in fully articulating the sensations, perceptions and discomforts that such situations can cause.

On more than one occasion, I have read that health professionals have mentioned that the experience of previous sufferers can be invaluable in helping to alleviate the sufferings of people who are suffering from such effects, in that a previous sufferer can readily identify with someone else’s present experience of these sensations, possibly more effectively than can a health professional who can understand the verbal description of the perception and awareness changes, but who has not experienced such things for themselves.

A further complication, when relying on the use of the spoken or written word to describe very subtle but also very profound effects, is brought about by the joint or disjointed understanding of words themselves. Even when the words used share the same common language, there can be semiotic, semantic and symbolic mismatches between what the speaker means and what the listener comprehends.

Given that medical, scientific and well-being discourses take place across international space – whether in published, televisual or online forum formats – such mismatches can be amplified: even to the point that - as an educator working in international and multi-cultural environments - I have been informed that certain languages have words, phrases and terms for things and concepts, and that those words, phrases and terms simply do not exist in other languages.

Added to this may remain the possibility that the shared first language of the speaker and listener may not have sufficiently adequate words to fully express the experience of certain effects, feelings and sensations: without even involving other languages. Given that it also seems to be the case that human beings throughout the world can encounter similar experiences based in physiologically shared circumstances and situations, and that even local languages can remain inadequate in fully conveying those experiences to others around them, many people can find themselves thrown into an engagement with – to paraphrase H P Lovecraft’s short story – The Unnameable.

There is an amount of research and resultant literature that suggests that certain life experiences – as recorded in ancient, traditional and historically recorded folk tales, legends and myths – are hardwired into the human brain and have been hard-wired in there since time immemorial. Basic storylines and plots, as studied within literature, theatre and film, indicate that human experience of the outer and inner worlds is shared in terms of the range of sensations, emotions and responses; and that is has been for at least as long as recorded history. Literature, theatre and artistic imagery have depicted these sensations, emotions and responses in accessible and enduring forms across historical and geographical fields.

During the earlier days of the development of the internet, a popular jibe against perceived over-use and reliance on the world-wide-web was that it encouraged the idea of solipsism in overenthusiastic browsers. Much has been written about the concept of solipsism as a philosophical idea that a person’s own mind is the only thing that that person can be sure exists, and that all else is just a construct of the workings of that person’s mind.

Whilst it can be quite challenging and possibly amusing to argue the physiological, environmental and philosophical cases for and against the possibility of a solipsist view of existence, there are other sensations, symptoms, and effects that can impose the more frightening and isolation-based aspects associated with an unwelcome, unpredictable and non-negotiable, imposed solipsism.

Depersonalisation, disassociation and other named effects/ side-effects of such conditions of illness, stress, fatigue, and medical treatments seem to be able to generate not only passing bouts of an imposed solipsist, isolated experience of the world around a person, but an ongoing, repetitive phenomenon that can drain energy, enthusiasm, confidence and engagement from a person as they spend large amounts of energy and determination to undertake actions in the world around them that they once performed naturally.

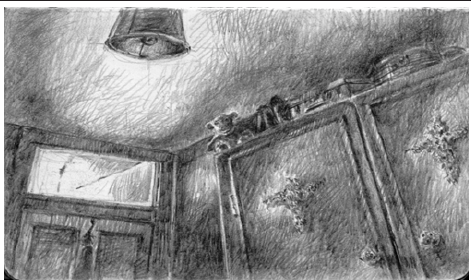

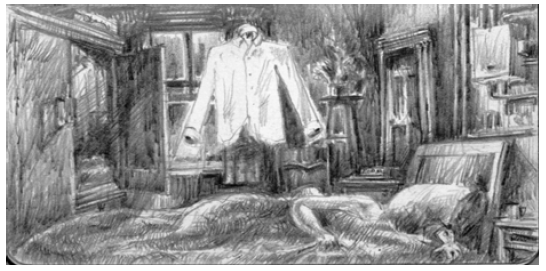

The rationale behind the production of this set of drawings was formed over time, as a way of attempting to communicate - in visual terms - that which has been described in verbal and - more often - written terms as relating to the effects of depersonalisation as caused by certain healthbased conditions and by the side effects of certain medications.

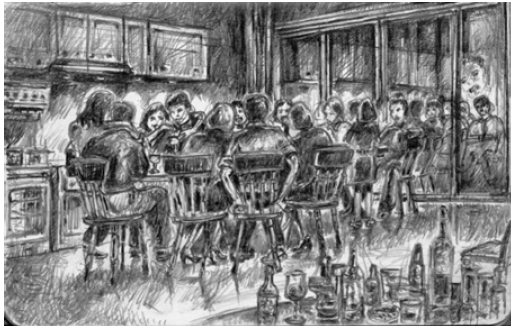

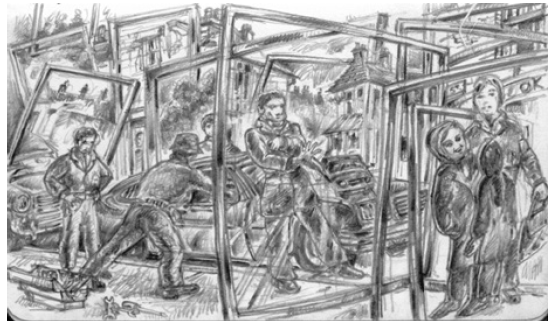

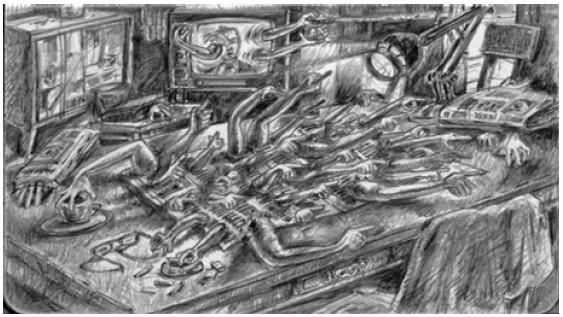

The drawings are placed below. Interestingly, when I was organising the print-outs of the drawings, people passing by began to stop and to take photographs of the drawings. On asking if they were interested in the drawings, the reply took the form of, ‘the drawings are sort of ok, but I’m mainly interested because they show what’s going on in my life.’ (Figure 1 to Figure 6)

Figure 3:Depersonalisation At The Dinner Table – Pencil – 2012, Unpredictable depersonalisation effects.

Figure 6:Two-Dimensional Saturday Afternoon – Pencil – 2018, Sound and vision perspective perception.

In Act 5 of Scene 1 of [1] Nothing by William Shakespeare, Leonato says,

‘For there was never yet philosopher

That could patiently endure the toothache’

In this passage, the character of Leonato is pushing against the stoicism of philosophy with regard to physical pain and discomfort [2].

Toothache is a common phenomenon, as Leonato states, but it is generally describable and can be understood, and a sufferer can empathised with by others who have had similar experiences [3]. The sufferer can also understand and anticipate – with access to the correct treatment – a pain-free resolution to their predicament. The subject of the drawings above relates to more subtle, indefinable and sometimes nondescribable but nonetheless life-disturbing effects that are not so readily identified in straightforward physical terms and therefore do not seem to have readily identifiable paths of resolution. The drawings above form part of an exploration into ways of describing such subtle but profound experiences and sensations by adding to the verbal and written forms in place [4].

References

- Much Ado About Nothing, Act 5 Scene p. 31-38.

- Christopher Brooker (2004) The Seven Basic Plots, Why We Tell Stories, published Bloomsbury.

- H P Lovecraft (1923) The Unnameable, published Weird Tales.

- All drawings produced by John Robert Burns.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.